What is Butoh Dance? Training Methods and Benefits for Performers

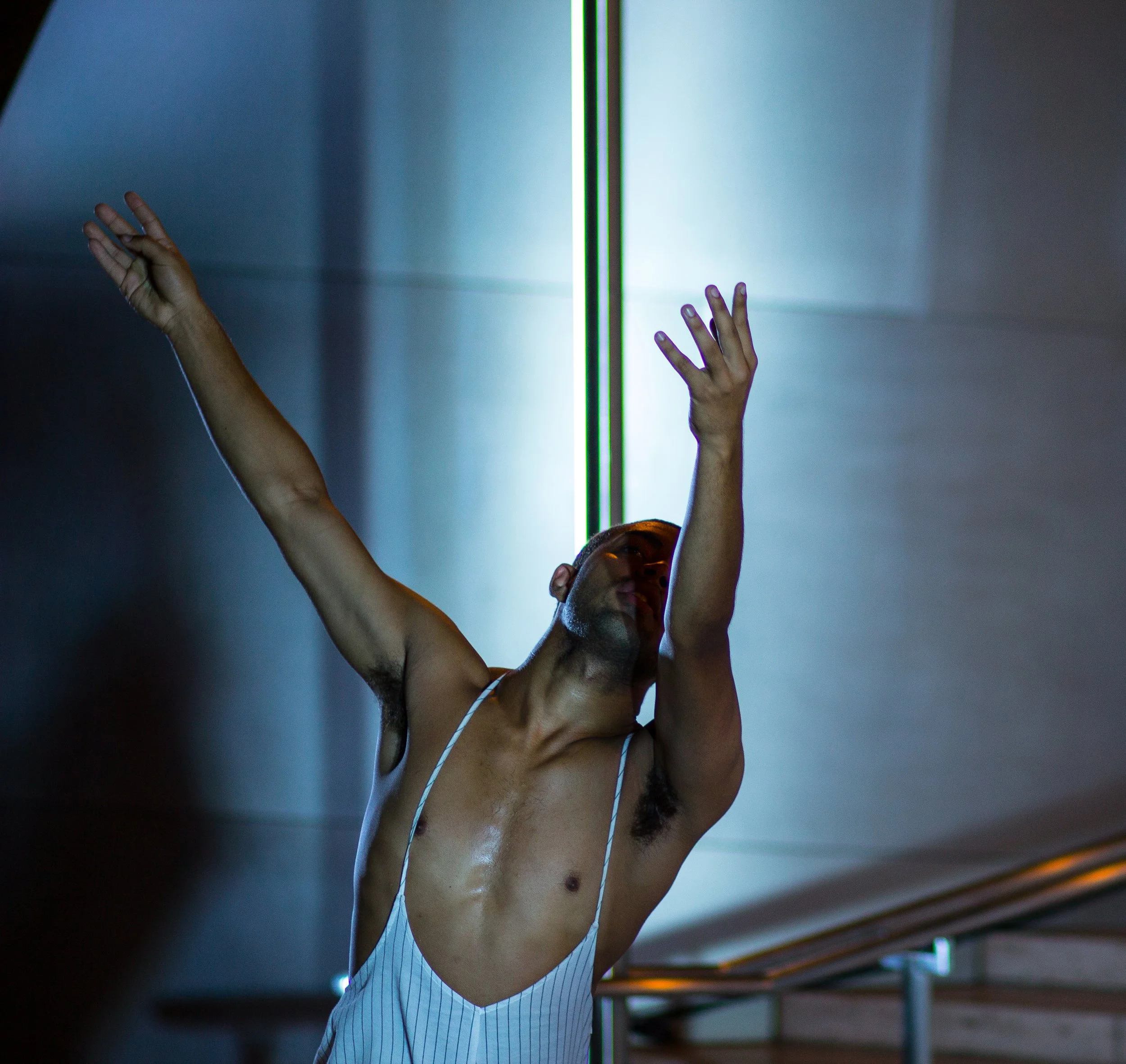

/Imagine a dancer moving so slowly that each gesture seems to emerge from the depths of the earth itself. Their body, painted white, transforms before your eyes—becoming wind, stone, an ancient creature, pure emotion made visible. This is Butoh, a Japanese dance theater form that continues to captivate and challenge performers around the world. Unlike conventional dance that prizes technical precision and aesthetic beauty, Butoh invites us into the grotesque, the vulnerable, and the profoundly human aspects of movement that other forms often polish away.

Butoh emerged in post-World War II Japan as a radical rebellion against both traditional Japanese dance and the Western ballet that was being imported into Japanese culture. Founders Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno created something entirely new—a dance that embraced darkness, transformation, and the primal aspects of human existence. In my own training and work as a movement director and somatic practitioner in Los Angeles, Butoh has profoundly shaped how I understand authentic movement and help performers access deeper layers of expression. The principles I learned from Butoh continue to inform my teaching across all modalities, from working with actors on character embodiment to guiding wellness clients through somatic awareness.

What is Butoh?

Butoh, sometimes called "dance of darkness" or "dance of the dead," was founded by Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno in 1950s and 1960s Japan. These pioneers were responding to the trauma of war, the rupture of traditional Japanese culture, and a desire to create something that expressed the full spectrum of human experience—including what polite society preferred to keep hidden. Butoh became a container for exploring the grotesque, the taboo, the primal, and the transformative aspects of being human. It was never meant to be pretty or comfortable to watch, but rather to be truthful and complete.

What distinguishes Butoh from other dance forms is its fundamental philosophy. This is not a technique focused on executing perfect lines, achieving impressive extensions, or mastering set choreography. Instead, Butoh is about metamorphosis, authenticity, and presence. Dancers are not performing steps—they are becoming something else entirely. The body is treated as a site of transformation rather than a tool for executing predetermined shapes. Where ballet seeks lightness and transcendence, Butoh embraces weight, earthiness, and the body's connection to mortality and decay.

Visually, Butoh is often immediately recognizable. Performers frequently appear with white body paint covering their skin, moving in extreme slow motion with contorted postures and intense facial expressions. But these are aesthetic choices that emerged from the form's deeper principles, not requirements. The white paint can represent a return to a pre-birth state, a blank canvas for transformation, or simply a way of making the body strange and otherworldly. The slow motion is not an effect but a training tool that reveals the infinite universe of micro-movements within every gesture.

At the heart of Butoh training is the use of imagery and metamorphosis. Rather than learning set steps or combinations, Butoh dancers work with vivid internal imagery that the body responds to organically. A teacher might guide you to imagine you are becoming wind moving through grass, transforming from human to stone, melting like ice, or growing from the earth like a plant pushing through soil. Your body responds authentically to these images rather than executing choreographed movements. This approach bypasses the thinking mind and allows the body's innate wisdom to emerge. In my own teaching, I often use this principle to help actors find authentic physical choices for characters or to help clients access new movement patterns that aren't constrained by habitual ways of moving.

The practice of slowness and time distortion is another foundational element of Butoh training. Dancers train in extreme slow motion, sometimes taking minutes to complete a single gesture. This is not simply about moving slowly—it's about discovering the infinite gradations of movement that exist between two positions. When you slow down to this degree, you become aware of micro-movements in your tissues, the subtle shifts of weight, the small adjustments that usually happen unconsciously. This practice develops extraordinary kinesthetic awareness and control while teaching performers to inhabit each moment fully rather than rushing toward the next position or the end of the phrase.

Butoh training also involves working with darkness and shadow—the aspects of human experience we often avoid or suppress. This means exploring uncomfortable emotions, the grotesque, vulnerability, aging, death, and transformation. It's important to understand that this is not about being "dark" for shock value or to seem edgy. Rather, it's about completeness and authenticity. We all contain the full range of human experience, and Butoh creates a container where performers have permission to explore aspects of themselves they might otherwise keep hidden. This work can be profoundly liberating because it removes the pressure to be beautiful, likeable, or palatable. For actors, this permission to explore the uncomfortable can break through performance clichés and access raw, truthful character states.

In Butoh, the body becomes landscape and material rather than a vehicle for self-expression. This is a subtle but crucial distinction. Instead of using your body to express your personality or emotions in a conventional sense, you allow your body to become a site of transformation. The ego and individual personality step back, and something more archetypal or elemental can emerge. You might become the memory held in your bones, the collective experience of all bodies, or pure energy taking form. This approach connects to the somatic understanding that our bodies hold wisdom and memory beyond our conscious minds.

Finally, Butoh emphasizes improvisation and radical presence. While some Butoh pieces have structured elements, the form values authentic response in the moment over perfectly executed choreography. Training focuses on developing the performer's ability to be fully present and responsive to internal imagery, the space, other performers, and the audience. This requires tremendous concentration and a willingness to not know what will happen next—to trust the body's intelligence and allow movement to emerge organically.

Why Butoh Training is Valuable

For actors, Butoh training offers invaluable tools for full-body expressiveness that goes far beyond facial acting or gesture. Many actors are trained primarily from the neck up, with the body serving mainly as a support system for the face and voice. Butoh reverses this, making the entire body an expressive instrument. The practice helps actors access raw, authentic emotional states without relying on conventional acting techniques that can sometimes feel manufactured. When you've trained in becoming wind or stone, when you've explored the grotesque and vulnerable in your own body, you develop a capacity for character transformation that is visceral and complete.

Butoh also helps actors break through performance habits and clichés. We all develop patterns—ways we habitually express anger, sadness, or joy. These patterns can make performances feel safe but predictable. Butoh's emphasis on working from imagery and allowing unexpected movement to emerge disrupts these habits and opens new possibilities. I've seen actors have breakthrough moments in Butoh-informed work where they discover physical choices for characters that surprise even themselves—choices they never would have found through conventional character analysis or rehearsal methods.

For dancers, Butoh training offers a powerful way to break technical habits and discover new movement vocabularies. Dancers who've trained extensively in ballet, modern, or contemporary techniques have developed sophisticated skills, but they can also become constrained by these techniques. Butoh gives permission to move in ways that would be "wrong" in other forms—to be awkward, to embrace ugliness, to move without concern for aesthetic line. This freedom can be revelatory, opening up movement possibilities that technical training may have closed off. The practice also deepens the connection between internal state and physical expression, so that movement becomes more than shapes in space—it becomes an authentic manifestation of what's happening inside.

Butoh complements other somatic practices beautifully. For dancers already working with modalities like Body-Mind Centering, Authentic Movement, or Ideokinesis, Butoh provides a performance context for somatic awareness. It's one thing to explore subtle internal sensations in a studio setting; it's another to bring that awareness into a performance context where you're transforming those sensations into visible movement. Butoh creates a bridge between private somatic exploration and public performance.

For anyone seeking embodiment—whether they identify as a performer or not—Butoh training develops profound body awareness. The slow-motion work, the attention to imagery and sensation, and the permission to explore the full range of human experience through movement all cultivate a deeper relationship with your physical self. Many people find that Butoh-informed movement work provides a safe container to explore difficult emotions that might be hard to access through talk therapy alone. There's something about moving through grief, rage, or fear—literally embodying these states and allowing them to transform—that can be therapeutic and liberating in ways that purely cognitive approaches cannot achieve.

How Butoh Relates to Other Somatic Practices

In my own work integrating multiple somatic modalities, I've found deep connections between Butoh and practices like Body-Mind Centering, Authentic Movement, and Laban Movement Analysis. Body-Mind Centering explores how different body systems—skeletal, organ, fluid, nervous—inform movement quality and experience. Butoh's use of imagery often taps into these same systems intuitively. When you imagine becoming water or moving from your bones, you're accessing the same principles that BMC approaches more anatomically.

Authentic Movement, a somatic practice developed by Mary Starks Whitehouse and later Janet Adler, involves moving with eyes closed while following internal impulses, with a witness holding space. This practice shares Butoh's emphasis on authentic response rather than predetermined choreography, though Authentic Movement typically happens in private therapeutic contexts while Butoh is inherently performative. Both practices trust that the body has its own intelligence and that meaningful movement emerges when we stop trying to control or choreograph every moment.

I often integrate Butoh principles into my teaching across all modalities. Whether I'm coaching someone in Pilates, guiding a Gyrotonic session, or working with an actor on movement for a role, the Butoh understanding that the body can transform, that slowness reveals depth, and that imagery unlocks authentic movement—these principles enrich whatever technique we're working with. The somatic foundation beneath Butoh's sometimes shocking aesthetic is really about presence, authenticity, and the body's innate wisdom.

Getting Started with Butoh

If you're interested in exploring Butoh, it's helpful to know what to expect. A Butoh class or workshop is typically very different from a technique-based dance class. You won't learn set combinations or be corrected on the "right" way to execute movements. Instead, you'll be guided through imagery, invited to explore sensations, and encouraged to discover your own authentic responses. Some people find this liberating; others find it disorienting at first, especially if they're used to more structured movement training.

The most important thing to understand about Butoh is that there is no "doing it right." This can be challenging for people who are achievement-oriented or who derive satisfaction from mastering techniques. Butoh asks you to let go of mastery and perfection and instead embrace exploration, vulnerability, and not-knowing. The practice is about discovering what wants to emerge from your body in this moment, with this imagery, in this space—not about replicating what the teacher does or achieving a particular aesthetic.

If you're coming from other dance backgrounds, be prepared for Butoh to feel very different. There's less emphasis on musicality, rhythm, or even coordination in the conventional sense. The work is intensely internal and focused on transformation rather than performance in the traditional way. At the same time, this internal focus paradoxically creates performances that are often riveting to watch because of their authenticity and commitment.

Butoh remains relevant and valuable precisely because it offers something that conventional movement training often doesn't—permission to be complete, to explore the shadow alongside the light, to move from a place of authentic transformation rather than technical execution. In a world that often prioritizes polish, productivity, and perfectionism, Butoh creates space for the messy, slow, vulnerable, and profound aspects of being human in a body.

Whether you're an actor seeking new tools for character embodiment, a dancer wanting to break through technical habits, or someone simply interested in deepening your relationship with movement and embodiment, Butoh-informed practices can open unexpected doors. The principles of working with imagery, embracing slowness, allowing transformation, and trusting the body's intelligence are applicable far beyond the Butoh performance aesthetic.

If you're interested in exploring Butoh-informed movement work, I offer private sessions and workshops in Los Angeles that integrate Butoh principles with other somatic practices. Whether you're preparing for a role, developing your movement practice, or seeking embodied healing and growth, I'd be honored to guide your exploration. Contact me to learn more about upcoming workshops or to schedule a private session.